Ethiopia Opens Africa’s Largest Hydroelectric Dam to Egyptian Protest

Ethiopia officially inaugurated Africa’s largest hydroelectric dam on Tuesday, a project that will provide energy to millions while deepening a rift with downstream Egypt that has unsettled the region.

Ethiopia, the continent’s second most populous nation with over 120 million people, sees the $5 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) on a tributary of the Nile as central to its economic ambitions.

The dam’s output has gradually increased since the first turbine was turned on in 2022, and it reached its maximum 5,150 MW of power on Tuesday. That puts it among the 20 biggest hydroelectric dams in the world, at about one-quarter of the capacity of China’s Three Gorges Dam.

At a ceremony on Tuesday at the site in Guba, an Ethiopian fighter jet flew low over the mist from the dam’s white waters, which plunge 170 metres (558 feet).

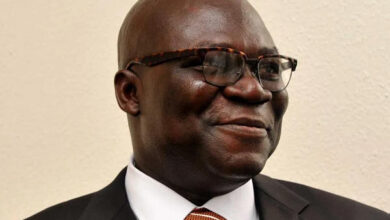

Beneath the canopy of a giant Ethiopian flag, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed addressed a crowd of dignitaries including the presidents of Somalia, Djibouti and Kenya.

“To our (Sudanese and Egyptian) brothers; Ethiopia built the dam to prosper, to electrify the entire region and to change the history of black people,” Abiy said. “It is absolutely not to harm its brothers.”

Abiy has said the dam will improve access to electricity for the almost half the population who had none as recently as 2022, and export the surplus to the region.

The dam’s reservoir has flooded an area larger than Greater London, which the government says will provide a steady water supply for irrigation downstream while limiting floods and drought.

DOWNSTREAM NEIGHBOURS FEAR WATER SHORTAGES

Ethiopia’s downstream neighbours, however, have watched the project advance with dread since construction began in 2011.

Egypt, which built its own Aswan High Dam on the Nile in the 1960s, fears the GERD could restrict its water supply during droughts, and could encourage the construction of other upstream dams.

Its Foreign Ministry wrote to the U.N. Security Council saying the inauguration of the dam violated international law.

Cairo has bitterly opposed the dam from the start, arguing that it violates water treaties dating back to the early part of the last century and poses an existential threat.

Egypt, with a population of about 108 million, depends on the Nile for about 90% of its fresh water.

Egypt says it reserves the right to “take all the appropriate measures to defend and protect the interests of the Egyptian people”.

While Egypt has refrained from any direct reprisals against Ethiopia, it has drawn closer in recent years to Addis Ababa’s rivals in the Horn of Africa, notably Eritrea.

Sudan, meanwhile, has joined Egypt’s calls for legally binding agreements on the dam’s filling and operation – but could also benefit from better flood management and access to cheap energy.

ETHIOPIA SAYS DAM IS NOT A THREAT

Ethiopia has been filling the reservoir in phases since 2020, arguing that it would not significantly harm downstream countries.

Independent research shows that so far, no major disruptions to downstream flow have been recorded, noting favourable rainfall but also the cautious filling of the reservoir during wet seasons over a five-year period.

In Ethiopia, which has faced years of internal armed conflict, largely along ethnic lines, the GERD has proven a source of national pride, said Mekdelawit Messay, an Ethiopian water researcher at Florida International University

“It has been a banner to rally under, and it shows what we can achieve when unified.”

Local media say 91% of funding came from the state, and the remaining 9% from Ethiopians buying bonds or making donations.

Sultan Abdulahi Hassan, a farmer who lives near the dam, said the project had brought electricity to his village.

“We now have refrigerators. We can drink cold water. We now use electricity for everything,” he said at the launch.

While the extra power will help the country’s burgeoning bitcoin mining industry, most rural Ethiopians may have to wait a little longer to benefit.

Access to electricity in rural areas is often constrained by underdeveloped transmission networks. While urban areas had a 94% electrification rate as of 2022, just 55% of the overall population had electricity, according to the World Bank.

REUTERS